Nrupa Borkar a,*, Huiling Mu a, René Holm b

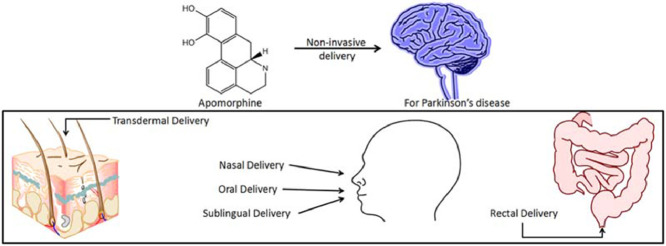

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Apomorphine, Drug delivery, Parkinson's disease, Alternative apomorphine therapy, Non-invasive delivery, Excipients

Abbreviations: PD, Parkinson's disease; SEDDS, Self-emulsifying drug delivery system; L-dopa, Levodopa; PAA-cys-2MNA, poly(acrylic acid)-cysteine-2-mercaptonicotinic acid

Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a chronic debilitating disease affecting approximately 1% of the population over the age of 60. The severity of PD is correlated to the degree of dopaminergic neuronal loss. Apomorphine has a similar chemical structure as the neurotransmitter dopamine and has been used for the treatment of advanced PD patients. In PD patients, apomorphine is normally administered subcutaneously with frequent injections because of the compound's extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism. There is, hence, a large unmet need for alternative administrative routes for apomorphine to improve patient compliance. The present review focuses on the research and development of alternative delivery of apomorphine, aiming to highlight the potential of non-invasive apomorphine therapy in PD, such as sublingual delivery and transdermal delivery.

1. Introduction

The earliest reported synthesis of apomorphine was described by Arppe in 1845 and later by Matthiesen and Wright in 1869, which involved reacting morphine with hydrochloric acid or sulfuric acid, respectively, to obtain apomorphine [1]. Apomorphine found its early use in veterinary therapeutics to treat issues associated with farmyard animal behavior. By 1874, it was known that apomorphine had effects on the central nervous system along with emetic effects [1], [2]. In human medical use, the compound was recommended as an emetic, sedative, as well as a treatment for narcotic and alcohol addiction [3]. Weil in 1884 suggested apomorphine for its potential use in treating Parkinson's disease (PD) [4], [5]. Schwab and coworkers and Cotzias confirmed Weil's suggestion, as they found a significant decrease in tremors and rigidity associated with PD in humans [6], [7], [8], [9]. In today's medical treatment, subcutaneous apomorphine is used for the treatment of advanced PD in patients undergoing motor disabilities that do not respond to other PD treatments. There is a large unmet need for alternative apomorphine delivery systems, as this treatment is provided by multiple subcutaneous injections daily. This review covers the importance of apomorphine in PD management and emphasizes the challenges with apomorphine therapy for PD patients. The present review also aims at highlighting some key research developments in the area of non-invasive delivery of apomorphine.

2. Physicochemical properties of apomorphine

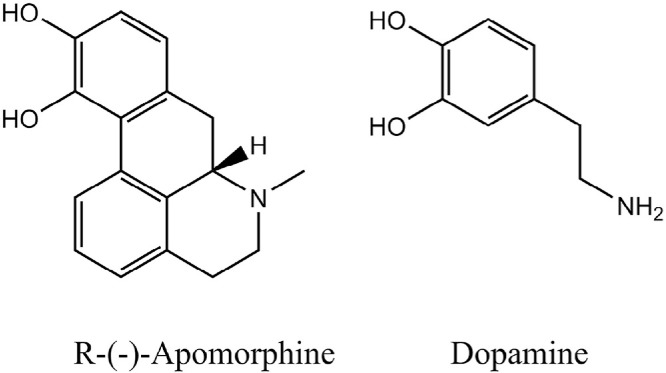

Apomorphine (6-methyl-6αβ-noraporphine- 10,11-diol) belongs to the class of β-phenylethylamines sharing structural similarities to the neurotransmitter, dopamine, both having a catechol moiety (Fig. 1). Apomorphine is a chiral molecule (MW: 267.32 Da). The R-form is a dopamine agonist, while the S-form of the molecule may possess anti-dopaminergic activity [10], [11].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of R-(-)-apomorphine and dopamine.

Apomorphine is water-soluble with an intermediate lipophilicity represented by a log P of 2.0 [12]. The compound has two pKa values, at 7.0 and 8.9 [13], and it is generally available as the hydrochloride salt. The hydrophilic character of apomorphine allows it to be solubilized and therefore, formulated as an aqueous solution. Moreover, it is readily mixed in tissue fluids and can be absorbed into the systemic circulation and subsequently cross the lipophilic blood-brain barrier [14].

3. Therapeutic uses of apomorphine

Apomorphine has been used in the treatment of several ailments. Table 1 illustrates the various apomorphine products currently available on the market. In veterinary practices, apomorphine is utilized as an emetic agent, which induces vomiting as a part of managing poisoning in dogs and other animals. Apomorphine acts on the dopamine receptors in the ‘chemoreceptor trigger zone’ in the area postrema of the medulla oblongata as well as the receptor cerebrospinal fluid side [2].

Table 1.

Currently marketed apomorphine formulations.

| Product name | Company | Dosage form and route of administration | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apometic ® [15] | Forum Animal Health | Solution for subcutaneous injection | Emesis for veterinary practice |

| Uprima®, Ixense®, Spontane ®, TAK 251 [16] | Pentech Pharmaceuticals Inc. (originator and developer); Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. (developer) | Sublingual tablet | Erectile dysfunction |

| APO-go, Apokinon, Apokyn, Apomine, Britaject, KW-6500, Li Ke Ji, MOVAPO ® [17] | Britannia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (originator and developer); Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd. and US WorldMeds (developer) | Solution for subcutaneous injection | Parkinson's disease |

One of the prescribed uses of apomorphine is its application in male erectile dysfunction. Apomorphine has been demonstrated to be an effective erectogenic agent by stimulating the postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the hypothalamus [18], [19]. A sublingual apomorphine formulation has been reported to have 18–19 min as an onset time of erection requiring very low (<1.5 ng/dl) apomorphine concentrations at the site of action [19]. Apomorphine therapy in improving erectile response can be considered as a valuable alternative to other treatments for erectile dysfunction.

The predominant therapeutic use of apomorphine is its use in PD. PD is a debilitating disease which is characterized by chronic neurodegeneration of the striatal region of the brain causing a deficiency of neurotransmitter dopamine [20], [21]. Replacing the loss of dopamine by using dopamine agonist is the choice of treatment for many PD patients. Apomorphine, a potent dopamine agonist, is commonly used as rescue therapy in subcutaneous formulations in advanced stage PD patients. Apomorphine and its role in PD are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Apomorphine has demonstrated its therapeutic effects in treating Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease is characterized by a loss of memory and cognitive functions, which is attributed to hyperphosphorylated tau protein and amyloid β-protein [22]. Apomorphine increases amyloid β-protein degradation and protects neuronal cells from oxidative stress. Therefore, it restores memory function and improves pathology traits of Alzheimer's disease assessed in a mice model [23]. More such studies in the future might establish apomorphine as a novel therapeutic agent in treating Alzheimer's disease.

4. Parkinson's disease and its treatment

PD is one of the most common chronic neurodegenerative diseases affecting about 1% of the population over the age of 60 [20]. As aforementioned, the dopamine-secreting neurons in the nigrostriatal region of brain undergoes a progressive degeneration leading to a depletion of dopamine in patients with PD [21]. The low levels of dopamine in the striatum have several implications on motor abilities, such as rest tremor, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity, postural instability, and falls. The non-motor complications involving the non-dopaminergic brain regions, such as neuropsychiatric and autonomic disturbances, cognitive impairment, etc. generally surface as the disease progresses [20].

PD is yet incurable; however, various symptomatic therapies are available to improve the quality of life as well as longevity for the PD patients. The severity of PD correlates to the degree of dopaminergic neuronal loss. In order to understand the need for apomorphine in the treatment of PD, one must understand the usage of levodopa (L-dopa) in managing PD. L-dopa, a precursor of dopamine, is the most efficacious oral drug available for alleviating symptoms of early stages of PD. L-dopa (dihydroxyphenylalanine) is also an endogenous intermediate in the synthesis of catecholamine neurotransmitters. In contrast to dopamine, L-dopa can be absorbed across the blood-brain barrier and converted to dopamine in the striatum [24].

In early stages of PD, it has been shown that L-dopa eases several symptoms, such as freezing, somnolence, edema, and hallucinations [25]. However, long-term therapy with L-dopa is limited due to a decrease in its efficacy. The prolonged use of L-dopa also causes appearance of adverse effects of dopaminergic motor functions especially dyskinesia (impairment in voluntary movements) [26], [27] and wearing off (‘on–off’ phenomenon) [28]. The “on–off” phenomenon in PD refers to a switch between mobility and immobility, which occurs as a worsening of motor function or, much less commonly, as sudden and unpredictable motor fluctuations as the disease progresses. As a result, dopamine receptor agonists are used alone or in combination with L-dopa to delay the onset of motor complications. Dopamine agonists can also be effective in early PD, especially in cases where the disease occurs in “younger” patients, where dyskinesia is a greater risk [29], [30]. Dopamine receptor agonists stimulate the post- and presynaptic dopaminergic receptors [31].

4.1. Apomorphine therapy

More than 50% of Parkinson's disease patients develop ‘on–off phenomenon’ with a prolonged L-dopa use of greater than 5 years, which warrants the use of dopamine agonists such as apomorphine [32], [33]. Apomorphine, a mixed D1 and D2 dopamine agonist, predominantly finds its use as a rescue medicine to treat the ‘off’ period in L-dopa therapy. The D1 potency by apomorphine is exhibited by the catechol moiety [34], while the bulky aromatic part of the molecule may contribute to the affinity toward D2 receptors [35]. The potency of apomorphine and L-dopa has been shown to be comparable to each other [36], [37], [38]. Unlike oral L-dopa therapy, apomorphine is administered subcutaneous in the abdomen region as an intermittent injection or by continuous infusion using an infusion pump [39]. The avoidance of dyskinesia is a major advantage of apomorphine treatment over L-dopa therapy. However, apomorphine administration has several disadvantages such as nausea and vomiting; thus, requiring anti-emetics, which are often co-dosed (such as, domperidone) [40]. Additionally, subcutaneous apomorphine therapy may give rise to problems with patient compliance associated with needle phobia or local pain due to irritation and inflammation followed by a formation of subcutaneous nodules [41], [42], [43].

4.2. Challenges with apomorphine therapy

Although apomorphine has medical applications, its inherent instability poses a complication in clinical practice. Oxidation of apomorphine is one of the pharmaceutical challenges when it is formulated as an aqueous solution. Apomorphine spontaneously undergoes oxidative decomposition in aqueous solution to yield a bluish-green color in the presence of light and air [44], [45]. The catechol group of the apomorphine molecule is highly susceptible to oxidation leading to the formation of a quinone [44], [46], [47]. The decomposition of apomorphine is dependent on its concentration as well as the pH and temperature of the solution [44], [48]. The chemical half-life of apomorphine is reported to be 39 min under conditions similar to that of plasma (at 37 °C and pH 7.4) [48]. The additions of antioxidants, chelating agents, or alteration of the formulation pH are some of the approaches reported in the literature to prevent the autoxidation of the molecule [44], [49], [50].

Another major challenge associated with apomorphine is the deactivation upon metabolism of apomorphine after administration. The in vivo conversion from the R-form of apomorphine, which is pharmacologically active, to the S-form lowers the pharmacological activity of the molecule [51]. Additionally, apomorphine is metabolized via numerous enzymatic pathways predominantly in the liver, but also in the brain and tissue fluids [52]. Some of the metabolic pathways include sulfation, glucuronidation, and catechol-O-methyltransferase [51], [53], [54], [55], [56]. Moreover, a large pharmacokinetic variability is reported between PD patients after subcutaneous administration of apomorphine [53]. This inter-subject variability may be caused by the interactions of the drug and its various metabolites with plasma and tissue, which complicates the clinical dose setting [44].

The clinical utility of apomorphine upon oral administration is highly limited due to hepatic first-pass metabolism [57]. The oral absorption of apomorphine in rats with surgical portacaval venous anastomosis or shunting was reported to be similar to the absorption after subcutaneous application. In contrast, the sham operated rats with intact portal-hepatic venous circulation had undetectable tissue concentration of apomorphine [52]. This suggested that apomorphine was well absorbed when given orally, but underwent an extensive metabolism in the liver. The metabolic constraints can account for a poor oral bioavailability of less than 4% in PD patients [57].

Due to a high extent of apomorphine metabolism, a plasma half-life of about 32 min is reported after subcutaneous administration [48], [58]. This short plasma half-life necessitates a higher frequency of injections to maintain a concentration of apomorphine in the blood and subsequently, in the brain. A continuous subcutaneous infusion may be used if apomorphine subcutaneous injections exceed 7–9 times daily [40]. As mentioned previously, this causes inconvenience to patients with PD and often leads to patient non-compliance. Additionally, self-injection might prove difficult for patient in late stage PD during ‘off’ periods due to impairment of motor functions [59].

5. Drug delivery approaches for apomorphine

There is a high medical need for improving apomorphine bioavailability via various approaches and/or administrative routes to improve patient convenience and compliance. The sections below highlight the developments in non-invasive delivery of apomorphine, which are setting a pathway for the future of apomorphine therapy in PD.

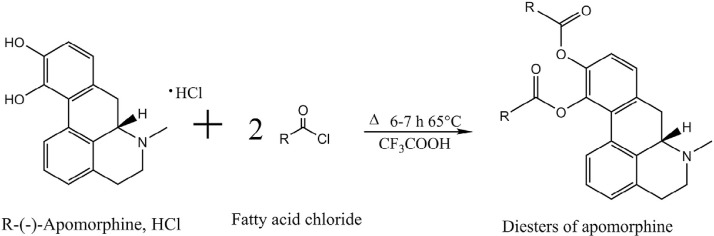

5.1. Chemical modification: Prodrug approach

Synthesizing prodrugs can be a method to improve physicochemical, biopharmaceutical and/or pharmacokinetic properties of an active compound. Prodrugs are derivatives of drug compounds which undergo enzymatic or chemical biotransformation to yield the pharmacologically active parent drug in vivo, which can exert its therapeutic action. One prominent site for derivatization for apomorphine is the catechol moiety in the molecule to synthesis diesters of apomorphine. Fig. 2 illustrates the general apomorphine esterification reaction yielding apomorphine diesters. Early literature on derivatization of apomorphine molecule was reported by Borgman et al., where diacetyl, dipropionyl, diisobutyryl, dipivaloyl, and dibenzoyl esters of apomorphine were synthesized [60], [61]. Stereotyped gnawing behavior and unilateral rotation were investigated upon intraperitoneal administration to rats. The duration of action of the diesters was significantly increased compared to that of free apomorphine. Apart from altering the pharmacokinetics, the advantage of esterification on the catechol moiety is that it inhibits oxidation of hydroxyl groups [62], thereby enabling the development of more chemically stable formulations.

Fig. 2.

General scheme of esterification of R-(-)-apomorphine to yield apomorphine diesters.

Although the first reported apomorphine esters were administered via an invasive intraperitoneal route, there are several studies of apomorphine esters which explored non-invasive routes of administration, such as the transdermal and oral route. Liu et al. investigated the transdermal delivery of two diesters of apomorphine: diacetyl and diisobutyryl apomorphine [12]. The diester prodrugs were more lipophilic than apomorphine and were determined as substrates to the esterases present in esterase medium, nude mouse skin homogenate, and human plasma. Apomorphine and its diester prodrugs formulated in lipid emulsions were investigated for their permeation across the skin of nude mouse (area of 0.785 cm2) using Franz diffusion cell. Diacetyl and diisobutyryl apomorphine yielded 11 and 3 folds higher fluxes, respectively, when compared to apomorphine. The results indicated a promising transdermal delivery of apomorphine by incorporating bioreversible lipophilic prodrugs in lipid-based carrier.

Apomorphine diester prodrugs have also been investigated for their oral delivery. Borkar and colleagues investigated the possibility of developing oral apomorphine formulations by synthesizing lipophilic derivatives of the molecule and incorporating them into lipid formulations [63]. The objective of utilizing lipophilic derivatives in lipid carrier was to stimulate the lymphatic drug transport, which will be further discussed in Section 5.2.1. Lipidifying apomorphine via prodrug was successfully demonstrated by obtaining highly lipophilic diesters: dilauroyl and dipalmitoyl apomorphine, which were 6.5 and 8.5 times more lipophilic (based on the logarithm of partition coefficient (log P) value), respectively, than their parent drug. This high lipophilicity of the diesters allowed them to be dissolved in lipid vehicles required to obtain lipid-based formulations. Additionally, the apomorphine diesters exhibited differences in their enzymatic degradation when incubated in biorelevant medium containing pancreatic extract. About 28% dipalmitoyl diester remained intact, while only 4% dilauroyl apomorphine was left undegraded after 5 min of incubation. It was suggested that the longer alkyl chain of dipalmitoyl apomorphine (C16) might have exhibited higher steric hindrance during enzymatic cleavage of the ester bond than dilauroyl apomorphine (C12). The need for enzymatic hydrolysis of the apomorphine diesters before initiation of the therapeutic action was also demonstrated by the presence of a lag time (about 30 min) in a 6-hydroxydopamine-induced rotational rat model [64].

Another study used R-(–)-11-O-valeryl-N-n-propylnoraporphine HCl as an oral apomorphine derivative to evaluate its motor effects on 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated marmosets [65]. The fast onset and prolonged duration of the therapeutic effects meant a reversal of motor deficits and improvement of dyskinesia in the PD marmoset model. These studies demonstrated that the various parameters in the apomorphine prodrug synthesis, such as chain length, branching and different types of substituents can be modified to alter the physicochemical and biopharmaceutical properties for the drug molecule.