Western blot

Radio immunoprecipitation assay lysis. buffer including protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the extraction of the total proteins of liver and small intestine, and the protein concentration was determined using BCA quantitative kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The total extracted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE for 2 h and then transferred to a PVDF membrane for 2 h. The membrane was incubated with T-TBS (containing 5% BSA) for 1 h and subsequently with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-CYP7A1 (1:1,000, Biorbyt orb539102, Cambridge, UK), anti-PPARα (1:1,000, Abcam ab126285, Cambridge, UK), anti-ABCG5 (1:1,000, Proteintech 27722-1-AP, Chicago, IL, USA), anti-NPC1L1 (1:500, Thermo Fisher PA5-72938, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-CPT1(1:500, Abcam ab128568, Cambridge, UK), and anti-GAPDH (1:10,000, Abcam ab181602, Cambridge, UK) as internal control at 4°C overnight. After being washed with T-TBS, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:5,000, Thermo Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:5,000, Thermo Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. Protein expression was visualized on X-ray films using SuperSignal® West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA). Image J 1.8.0 was used to analyze the optical density values of bands, and each test was repeated three times.

Isolation and characterization of serum extracellular vehicles

The cell fragments in the serum were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min, and the supernatant was transferred to Beckman L-100XP Ultracentrifuge (Brea, CA, USA) at 100,000 × g for 75 min and then discarded. The precipitate was washed and resuspended with PBS for another centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 75 min (24). After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was resuspended with 200 μl of PBS to obtain serum extracellular vehicles (EVs). Quantification was performed using BCA kits (Thermo Fisher Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA). In characterizing EVs, three or more proteins must be reported in at least a semi-quantitative manner, single vesicles must be examined, and the size distribution of EVs must be measured (25). EVs were characterized by TEM HT7700, and the average EV particle size was analyzed by Flow NanoAnalyzer N30E (Xiamen Fuliu Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China). EV-labeled proteins tetraspanins (CD9 and CD63) and endosome or membrane-binding proteins (TSG101) were quantitatively detected by Western blot.

QRT-PCR assay for miRNAs in serum extracellular vehicles

For the selection of miRNAs closely related to the mRNAs of lipid metabolism, the species was first selected as rats on miRDB.1 Several mRNAs related to lipid metabolism were then imported. One example is CYP7A1, that is, all miRNAs related to CYP7A1 gene were analyzed. For reliable results, all the miRNAs related to CYP7A1 gene obtained from the last website were inputted in another web site TargetScanMouse.2 Hundreds of related genes were obtained for each miRNA. CYP7A1 was searched in this list. If the results overlap, then this miRNA will be selected as an alternative. Finally, miR-21-5p, miR-30b-5p, miR-33-5p, miR-27a-3p, and miR-126a-5p were identified as possibly interacting with target genes PPARα, MTP, CYP7A1, ABCG5, and HMGCR, respectively (14).

First, serum EV miRNA was extracted as follows. EVs were added with 300 μl of binding buffer, shaken evenly, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a spin cartridge, and the precipitate was retained and added with anhydrous ethanol to obtain a final ethanol concentration of 70%. The mixture was transferred to the second spin cartridge and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 1 min. The waste was discarded, and the sample was centrifuged again at 12,000 g for another 1 min after 500 μl of wash buffer was added to the spin cartridge. The waste liquid was discarded, and the above steps were repeated. Idling centrifugation (12,000 g, 5 min) was performed to dry the adsorption column, and centrifugation was conducted at 12,000 g for 2 min. Finally, the spin cartridge was added with 50 μl of RNase-free ddH2O and then stored at –80°C after being placed at room temperature for 2 min (26). qRT-PCR was performed in line with the above steps. The reverse-transcription primer sequences are shown in Table 2, and the qRT-PCR primers are displayed in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Reverse transcription primer sequences of miRNAs.

| Gene | GenBank accession | Reverse transcription primer sequences (5′–3′) |

| rno-mir-27a-3p | MIMAT0000799 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGCGGAA |

| rno-mir-33-5p | MIMAT0000812 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTGCAAT |

| rno-mir-126a-5p | MIMAT0000831 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCGCGTA |

| rno-miR21-5p | MIMAT0000790 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTCAACA |

| rno-miR30b-5p | MIMAT0000806 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACAGCTGA |

TABLE 3.

Real-time PCR primers of miRNAs.

| Gene | Forward primer and universal primer (5′–3′) |

| rno-mir-33-5p-F | CGCGGTGCATTGTAGTTGC |

| rno-mir-27a-3p-F | GCGCGTTCACAGTGGCTAAG |

| rno-mir-126a-5p-F | GCGCGCATTATTACTTTTGGTACG |

| rno-miR21-5p-F | GCGCGTAGCTTATCAGACTGA |

| rno-miR30b-5p-F | GCGCGTGTAAACATCCTACAC |

| Universal reverse primer (micro-R) | AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT |

Double luciferase assay

293T cells in logarithmic growth phase were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected with Lipofectamine™ 3000 Transfection Reagent at approximately 60% confluence. Before transfection, the medium was replaced with a fresh one. MiRNA-30b-5p mimics and miRNA-126a-5p mimics were prepared at 20 pmol/well, and recombinant plasmid pmirGLO-MTP-WT or pmirGLO-MTP-MUT and pmirGLO-HMGCR-WT or pmirGLO-HMGCR-MUT were added at 500 ng/well. The 24-well plates with fresh medium were placed in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 8 h. After 48 h, each well was washed with PBS twice and added with 250 μl of 1 × PLB lysate before the cells were lysed at room temperature. Approximately 100 μl of LAR II was absorbed in a black 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 20 μl of lysis solution. After the reading of mixture was checked, Stop & Glo substrate (100 μl) was added within 10 s and the new reading was recorded again.

Gut microbiota composition analysis

Microbial DNA was extracted from rat cecal content samples with the Fast DNA SPIN kit (MPBIO, CA, USA) in accordance with the instructions. The V4–V5 region of the bacteria 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified by PCR under specific conditions (95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min) and using primers 515 F (5′-barcode-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3′) and 907 R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′); the barcode of which has an eight-base sequence unique to each sample. Amplicons were extracted from 2% agarose gels, purified with the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) and quantified using QuantiFluor™-ST (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The Purified PCR products were quantified by Qubit®3.0 (Life Invitrogen). The pooled DNA product was used to construct Illumina Pair-End library following Illumina’s genomic DNA library preparation steps. The amplicon library was then paired-end sequenced (2 × 250) on an Illumina Novaseq platform (Mingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). The image data files obtained by high-throughput sequencing were converted into sequencing reads, which were then stored in FASTQ files including their sequence information and sequencing quality information. For reliable results in subsequent analysis, the raw data were first filtered through Trimmomatic v0.33, CutAdapt 1.9.1 and custom Perl scripts were then used to identify and remove primer sequences, and high-quality reads without primer sequences were finally generated. USEARCH (version 103) was employed to assign sequences with ≥ 97% similarity to the same OTUs. Tukey’s method and R software were used for the comparison of alpha diversity index between samples (P = 0.05). Beta diversity analysis and mapping were performed on QIIME (27) to reveal differences and similarities among the samples as measured by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) with R software. LEfSe method was applied to compare the differential abundances of bacteria among groups at family and genus levels (28). Only those taxa with a log LDA score > 4 were considered.

Statistical analysis

Data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test using SPSS 18.0 (P < 0.05 indicated significant differences).

Results

Characterization of NFEG-microgel

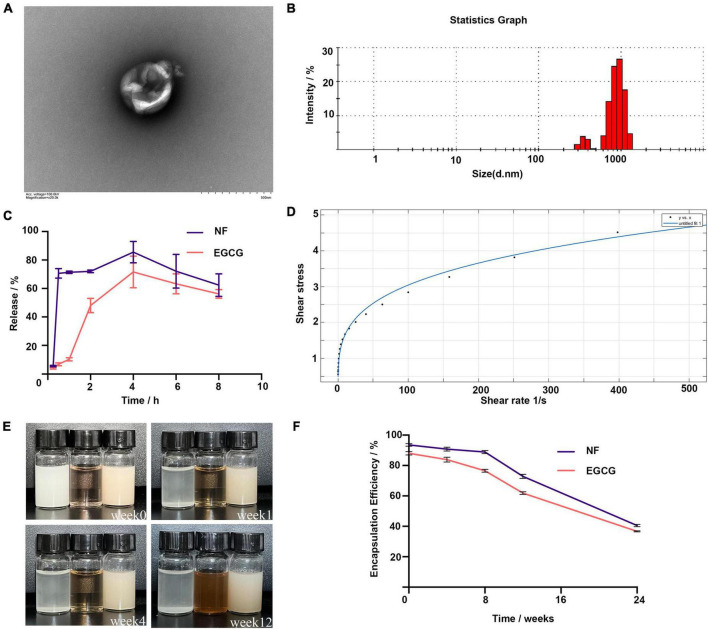

The encapsulation rates of NF and EGCG by NFEG-microgel were 90 and 86%, respectively, and that of NF by liposomes was 93.5%. The average particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of NF-liposome were 104.8 nm, 0.226, and +59.8 mV, respectively, and those of NFEG-microgel were 2595 nm, 0.532, and –41.6 mV, respectively. Absolute zeta potentials greater than 30 were considered as stable. The microstructural morphologies of NFEG-microgel were observed by TEM as shown in Figure 1A. All the microgels had regular spherical or subspherical shape with neat edges. The average particle size of NFEG-microgel was 0.5∼3.0 μm (Figure 1B), which was in line with the above results. According to the rheological data, the shear viscosity of NFEG-microgel decreased with the increase in shear rate. The mathematical power-law function model was fitted to the obtained data using the cf tool in MATLAB R2020a to determine the consistency index k and fluidity index n. The fitting coefficient R2 was 0.99, indicating that NFEG-microgel conforms to the power-law fluid, that is, it is a non-Newtonian fluid. The k value was 0.899, and the n value was 0.265. If n < 1 in power-law fluid, then NFEG-microgel is a fake plastic fluid (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of NFEG-microgel. (A) NFEG-microgel observed by TEM, (B) average particle size of NFEG-microgel, (C) simulated NFEG-microgel digestion in SGF and SIF, (D) rheological fitting curve, (E) storage of NFEG-microgel at 4°C for 12 weeks (from left to right, NF solution, EGCG aqueous solution, and NFEG were shown), and (F) encapsulation rates during storage for 24 weeks.

Release

The NF in NFEG-microgel had a good release ability under SGF and SIF conditions with release rates of 70.6% at 0.5 h in SGF and 85.5% at 4 h in SIF. A high release rate was maintained up to 8 h. However, the release characteristics of EGCG in NFEG-microgel differed from those of NF. EGCG was released slowly in SGF and reached about 48% release rate at 2 h. Meanwhile, NFEG-microgel entered the digestive SIF, promoting the sustained release of EGCG in the microgel. The release rate reached 71.5% at 4 h and remained high up to 8 h (Figure 1C). The microgels protected EGCG and ensure its slow and sustained release because chitosan coating can increase the adhesion of mucosa.

Storage stability

The storage stability of NFEG-microgel was evaluated by its apparent appearance upon storage at 4°C for 12 weeks. Figures 1E,F show that even after being stored for 12 weeks, the freshly prepared NFEG-microgel still showed good stability in terms of color, uniformity, and encapsulation rate and maintained 76 and 68% encapsulation rates for NF and EGCG, respectively. Meanwhile, NF solution of the same concentration dissolved in 0.5% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose exhibited precipitation at the 1st week, indicating the conventional suspension dosage form of NF had disadvantages such as uneven dispersion and instability. The same concentration of EGCG solution exhibited discoloration at the 4th week, indicating that the stability of conventional solution was poor (Figure 1E). In conclusion, NFEG-microgel increased the water solubility, dispersion, and stability of NF and enabled its sustained and stable release. Moreover, NFEG-microgel protected the storage stability of EGCG, which is easily oxidized and discolored when placed in a complex external environment. NFEG-microgel also inhibited the direct digestion and destruction of EGCG in the intestine due to the adhesion of chitosan to intestinal mucosa.

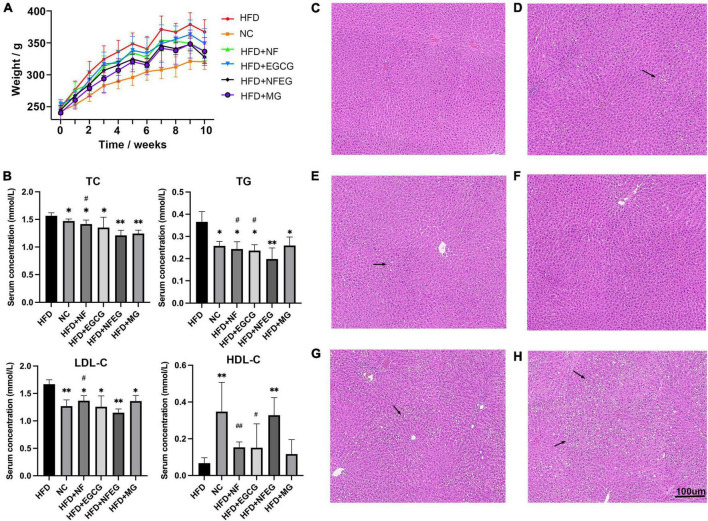

NFEG-microgel significantly reduced the body weight and ameliorated lipid metabolism disorder in high-fat diet rats

The liver of the rat in each group was photographed (Supplementary Figure 1). In terms of appearance, the liver of rat in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + NFEG, HFD + MG, and HFD groups was larger and showed different degrees of yellowing compared with that in the normal group. The liver color of the HFD + NFEG group was the closest to that in the normal group. The body weights of different groups showed an increasing trend. At the end of HFD feeding for 8 weeks, the body weight of rats was significantly higher in the HFD group than that in the NC group but lower than that in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + NFEG, and HFD + MG groups. The HFD + NFEG group showed the most remarkable reduction in body weight (Figure 2A). The total 8-week feed consumption in kilograms (kg) for the NC, HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + NFEG, HFD + MG, and HFD groups was 5.67, 5.31, 5.04, 5.61, 5.51, and 5.69 kg, respectively. According to these data, the normal diet consumption per day was consistent with the rising trend of body weight gain in the NC group. A slight decrease in HFD consumption per day was observed in the other groups from the 5th week to the last week. The trends of water intake per day were in accordance with the diet consumption, and no difference in weekly water consumption was found among the groups.

FIGURE 2.

Body weight, serum biochemical indexes and H&E staining in different treatment groups: (A) body weight of rats, (B) serum TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C concentrations, liver H&E staining (C) NC group, (D) HFD + NF group, (E) HFD + EGCG group, (F) HFD + NFEG group, (G) HFD + MG group, and (H) HFD group. (*P < 0.05) and (**P < 0.01) vs. HFD group; (#P < 0.05) and (##P < 0.01) vs. HFD + NFEG group.

As shown in Figure 2B, the NC, HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + NFEG, HFD + MG groups had significantly lower serum TC, TG, and LDL-C concentrations (P < 0.05) and significantly higher HDL-C content (P < 0.05) than the HFD group, except for the HFD + MG group whose HDL-C content showed no significant difference from that in the HFD group. The difference between HFD + NFEG and HFD groups was the most significant (P < 0.01). In particular, the HFD + NFEG group had significantly lower TC and LDL-C contents than the HFD + NF group and significantly different TG and HDL-C contents compared with those in the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups (P < 0.05).

Rat liver H&E staining results showed that the hepatocytes filled with large lipid composition had balloon-like changes, and the hepatocyte nuclei were constricted and deformed in the HFD group. Meanwhile, the amounts of lipid droplets and the degree of liver fat cavitation in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, and HFD + NFEG groups were reduced compared with those in the HFD group, indicating that HFD-induced hepatic fat accumulation could be reduced by NF and EGCG (Figures 2C–H). These results demonstrated that NFEG-microgel has a better effect on improving the lipid profile, hepatic steatosis, and liver injury than HFD or feeding with single package NF or EGCG-microgel.

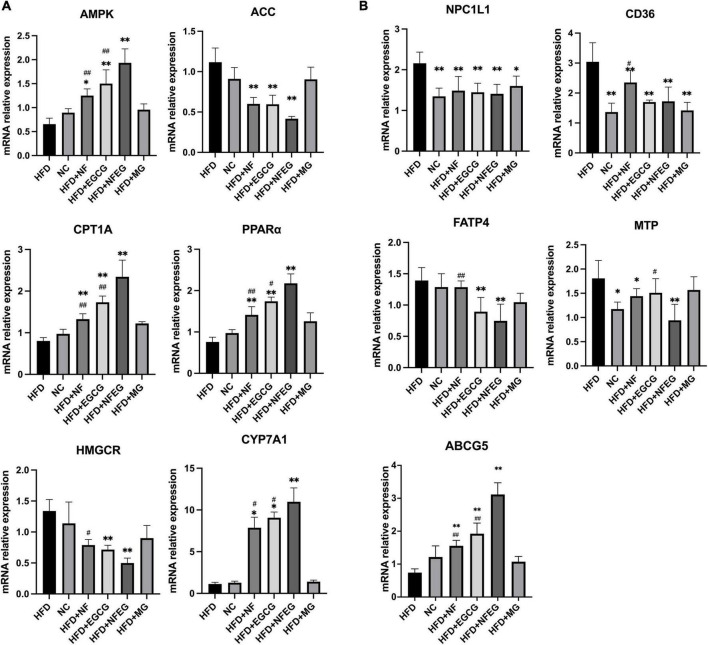

NFEG-microgel significantly regulated the mRNAs in liver and small intestine

Key genes associated with lipid metabolism in the liver and small intestine were detected, and differences were observed among the groups. HFD + NFEG had significant effects on liver PPARα, AMPK, ACC, CYP7A1, CPT1A, and HMGCR (P < 0.01) compared with HFD. The expression of AMPK, CPT1A (P < 0.01), and CYP7A1 (P < 0.05) genes in the HFD + NFEG group were significantly higher than those in the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups (Figure 3A). HFD + NFEG downregulated the expression of NPC1L1, MTP, CD36, and FATP4 and significantly repressed the downregulation of ABCG5 in the small intestine of HFD rats (P < 0.01). The HFD + NFEG group had significantly higher expression of ABCG5 gene (P < 0.01) and significantly lower expression of MTP genes (P < 0.05) compared with the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups. FATP4 expression in the HFD + NFEG group was significantly decreased compared with that in the HFD + NF group (P < 0.01). CD36 and FATP4 expression showed no significant differences between the HFD + EGCG and HFD + NFEG groups, indicating that EGCG mainly inhibited lipid absorption after its release in the intestine. In addition, the expression of NPC1L1 and CD36 in the HFD + MG group was as low as that in the HFD + NFEG group (Figure 3B), indicating that the blank microgel had a similar effect on lipid absorption.

FIGURE 3.

mRNA levels in rat liver and small intestine: (A) expression of AMPK, ACC, CPT1A, PPARα, HMGCR, and CYP7A1 in rat liver; and (B) expression of NPC1L1, CD36, FATP4, MTP, and ABCG5 in rat small intestine. (*P < 0.05) and (**P < 0.01) vs. HFD group; (#P < 0.05) and (##P < 0.01) vs. HFD + NFEG group.