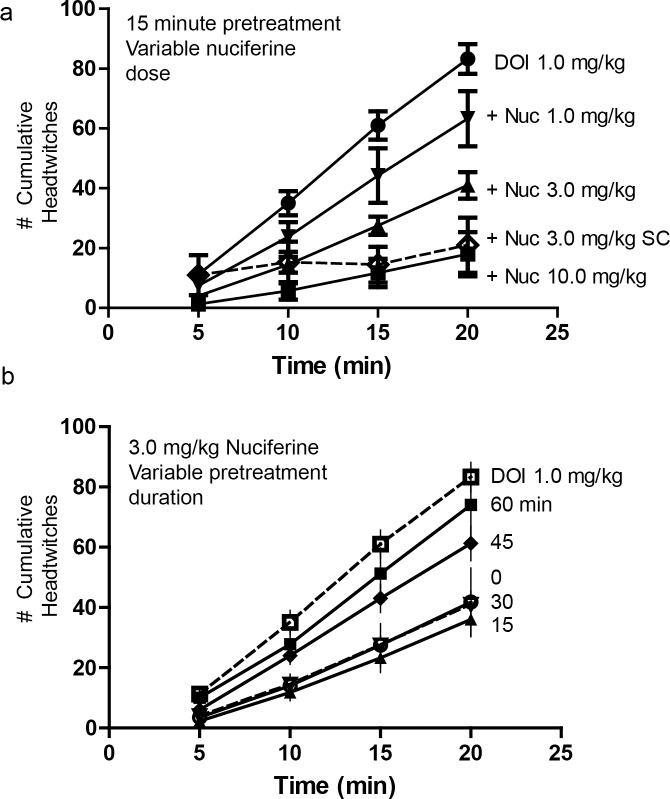

Fig 6. Inhibition of the 5-HT2A mediated, DOI-induced head-twitch response by nuciferine.

(a) Dose response curves of a 15-minute nuciferine pretreatment on the 1.0 mg/kg DOI-induced head twitch response. Solid lines indicate intraperitoneal administration of nuciferine. Dashed line indicates subcutaneous administration of nuciferine. Dose of nuciferine indicated to right of its associated data line. (b) Effect of nuciferine pretreatment time on the suppression of the DOI-induced head-twitch response. All pretreatments were administered intraperitoneally. DOI-alone condition provided as reference. Pretreatment time indicated to right of its associated data line. Data are presented as the mean number of cumulative head-twitches (y axis) at the given time point (x axis) (mean +/- s.e.m.; n = 3).

The time-course of 3 mg/kg nuciferine pre-treatment (i.p.) indicated that suppression of the DOI-induced head-twitches was most pronounced when the interval between the nuciferine and DOI injections was 15 min (Fig 6B). When the interval between nuciferine and DOI injections was varied, a RMANOVA found the main effect of time [F[9,54] = 334.913, p<0.001] and the time by pre-treatment interval [F[15,54] = 5.838, p<0.001] to be significant. Bonferroni analyses indicated that mice treated 45 or 60 min prior to DOI injection failed to show significant alterations in head-twitches compared to DOI-treated animals (Fig 6B). By contrast, mice treated 15 or 30 min prior to the DOI injection all had statistically significant (p<0.05) reductions in the numbers of head-twitches compared to mice given DOI at the 5, 10, 15, and 20-min sampling times. Moreover, nuciferine pretreatment at 15 min produced the most profound overall reductions in head-twitches relative to animals pretreated at 45 and 60 min and measured at 15 and 20 min sampling times, all of which were statistically significant (p<0.05). Collectively, these data demonstrate that nuciferine can antagonize DOI-induced head twitches and that these effects are time-dependent with the 15 min interval between nuciferine and DOI injection being the most effective.

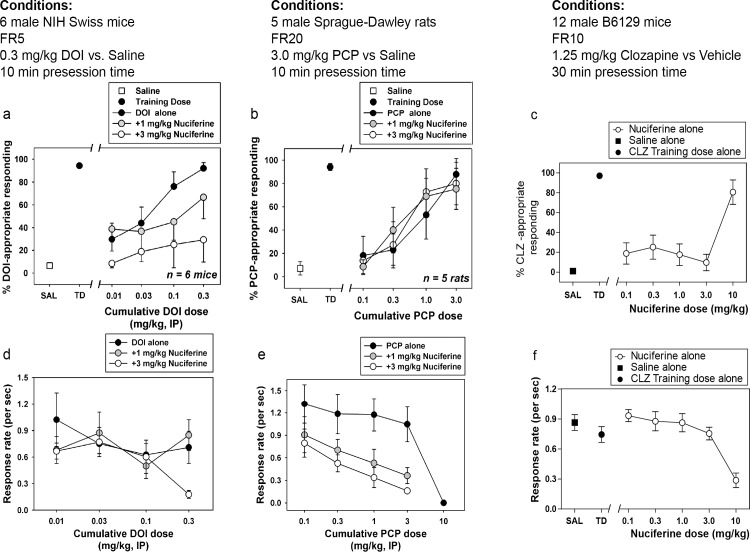

3.5 Drug discrimination

Dose-dependent generalization for the DOI training dose was observed when cumulative doses were administered alone, with cumulative doses of 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg producing full substitution (Fig 7A). In the presence of 1.0 mg/kg nuciferine, however, cumulative DOI doses only produced partial substitution, whereas in the presence of 3.0 mg/kg nuciferine, no cumulative dose of DOI substituted for the training dose, up to a dose that profoundly suppressed responding (Fig 7D). Although the overall ANOVA was significant (p<0.001), no within-dose pairwise comparisons reached statistical significance. Dose-dependent generalization for the PCP training dose was observed when cumulative doses were administered alone, with a cumulative dose of 3.0 mg/kg producing full substitution. In the presence of 1.0 or 3.0 mg/kg nuciferine, cumulative PCP doses produced similar substitution to PCP alone (Fig 7B). Although the overall ANOVA was significant (p<0.05), no within-dose pairwise comparisons reached statistical significance. In the clozapine-trained animals, a dose-dependent substitution for 1.25 mg/kg clozapine was seen at 10.0 mg/kg nuciferine (80.63% drug lever responding), with an ED50 value of 5.42 mg/kg (95% CI 3.09–9.48 mg/kg) while the lower doses tested (0.1 mg/kg–3.0 mg/kg) failed to produce substitution for clozapine’s discriminative cue (Fig 7C). In addition to a high percentage of responding on the clozapine-appropriate lever, 10.0 mg/kg nuciferine also produced significant rate suppression as compared to vehicle control points (p < 0.001) (Fig 7F).

Fig 7. Drug Discrimination studies of nuciferine.

(a,d) Nuciferine blocks the discriminative stimulus of DOI at doses that do not affect the rate of responding. (b,e) Nuciferine does not block the discriminative stimulus of PCP at any dose tested. (e,f) Nuciferine substitutes for clozapine (solid circles) but only at a dose that suppresses response rate (empty circles). Data are presented as % training-drug appropriate responding and response rate per second.

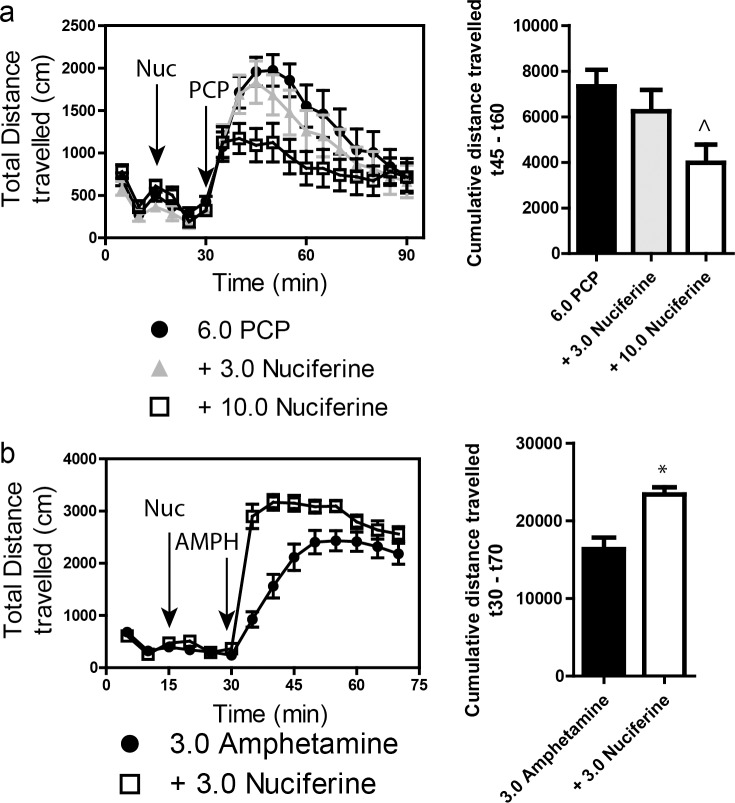

3.6 Locomotor activity

Stimulation of locomotor activity by 6.0 mg/kg PCP was significantly blocked by 10.0 mg/kg, but not by 3.0 mg/kg, nuciferine (Fig 8A. left panel). RMANOVA revealed a significant effect of time [F[17,765] = 30.553, p<0.001], and a significant time by treatment interaction [F[34,765] = 1.997, p<0.010]. Bonferroni corrections indicated that during the 0–30 min interval locomotion in all groups was similar. As expected, PCP stimulated locomotor activity from 35–90 min compared to baseline at 0–30 min (ps<0.001). Treatment with 3 mg/kg nuciferine prior to PCP failed to significantly alter the PCP-induced hyperlocomotion, whereas the 10 mg/kg nuciferine significantly depressed this locomotion compared to PCP-treated mice at 45–60 min (p<0.05). Nevertheless, the reductions in PCP-stimulated activity by 3 and 10 mg/kg nuciferine were not statistically different. When the results were presented as cumulative distance traveled between 45 and 60 min of testing, dose-dependent decreases in PCP-stimulated activity could be seen (Fig 8A, right panel). ANOVA found a significant effect of treatment [F[2,47] = 4.323, p<0.05] and Bonferroni tests confirmed that 10 mg/kg nuciferine significantly reduced locomotion compared to PCP (p<0.05). The 3 mg/kg dose decreased activity, but it was not significantly different from the PCP alone or the 10 mg/kg plus PCP group.

Fig 8. Locomotor studies of nuciferine.

(a) Nuciferine suppresses the PCP-induced hyperlocomotor response. Data are presented as total distance travelled in 5-minute bins (left) and as cumulative distance travelled between minute 45 and minute 60 (right). N = 18 mice; ^p<0.05, compared to PCP group. (b) Nuciferine (3.0 mg/kg, 15 minute pretreatment) enhances the hyperlocomotor effect of amphetamine (3.0 mg/kg) administration. N = 14 mice; * < 0.001 compared to Amphetamine group. Data are presented as above.

A second set of mice was used to assess the effects of 3 mg/kg nuciferine pre-treatment on amphetamine induced hyperlocomotion (Fig 8B, left panel). A RMANOVA revealed a significant effect of time [F[13,390] = 177.243, p<0.001] and a significant time by treatment interaction [F[13,390] = 14.625, p<0.001]. Bonferroni corrected comparisons found that activities between the two group at 0–30 min were not statistically different. All animals showed a significant increase in activity following amphetamine treatment compared to their baseline activities (p<0.001). Those mice given nuciferine prior to amphetamine treatment showed significantly higher motor activity between 35–50 min compared to those given amphetamine alone (p<0.05); however, responses after this time were not significantly differentiated. When the distance travelled in the open field for the 40 min following amphetamine treatment was aggregated, mice given nuciferine followed by amphetamine had heightened activity compared to those animals given amphetamine alone (Fig 8B, right panel) [t[1,30] = 4.014, p<0.001]. Together, these findings indicate that while nuciferine is capable of attenuating the hyperlocomotion induced by PCP, amphetamine induced hyperlocomotion is exacerbated by the compound.

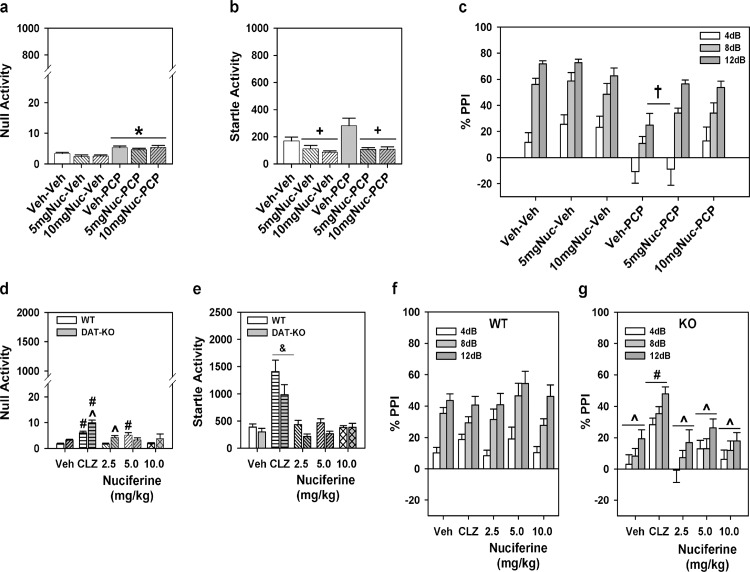

3.7 Pre-pulse inhibition

For the experiment with C57BL/6J mice a two-way ANOVA was applied with two levels of treatment: PCP (vehicle or VEH and PCP) and nuciferine (VEH and the two doses of nuciferine) constituted the 6 groups. A two-way ANOVA for null activity identified a main effect of PCP treatment [F(1,45) = 31.70, p<0.001], but the nuciferine treatments and the PCP by nuciferine interaction was not significant. Although Bonferroni corrected pair-wise comparisons noted that null activity was higher in the PCP-treated groups than in the respective vehicle/nuciferine groups (p<0.001), this activity was still less than 7% of the startle responses in the PCP-treated group (Fig 9A). A two-way ANOVA for startle responses also observed a significant main effect of nuciferine treatment [F(2,45) = 13.22, p<0.001]; the PCP treatment effect and the PCP by nuciferine interaction was not significant. Bonferroni post-hoc tests reported that startle responses for the 5 and 10 mg/kg nuciferine-treated groups were lower than those of the vehicle-treated groups (p<0.001; Fig 9B). RMANOVA for PPI revealed the within subjects main effects for prepulse intensity was significant [F(2,90) = 93.16, p<0.001]; the prepulse-intensity by PCP treatment, prepulse-intensity by nuciferine treatment, and the prepulse-intensity by PCP by nuciferine treatment interactions were not significant (Fig 9C). Bonferroni tests demonstrated that the response to the 4dB prepulse was lower than that for the 8 and 12dB prepulse responses (p<0.001) and that the 8dB response was lower than that for the 12dB response (p<0.001). Regardless of prepulse intensity, the between subjects main effects for the nuciferine [F(2,45) = 3.43, p<0.05] and PCP treatments [F(1,45) = 33.85, p<0.001], as well as the nuciferine by PCP treatment interaction, were significant [F(2,45) = 3.31, p<0.05]. Decomposition of the interaction observed that PPI in the vehicle-vehicle, 5 mg/kg nuciferine-vehicle, and 10 mg/kg nuciferine-vehicle groups were not differentiated from each other, but that PPI in the PCP-vehicle group was suppressed relative to these controls (p<0.001). Despite this fact, mice given nuciferine prior to PCP had higher PPI than the PCP-vehicle groups (p<0.05) and the 10 mg/kg nuciferine-PCP group was not statistically different from the respective control. Thus 10/mg/kg nuciferine rescued the PCP-disrupted PPI.

Fig 9. PPI responses to nuciferine in mouse models of hypoglutamatergia and hyperdopaminergia.

Nuciferine rescued PPI in the former, but not in the latter model. (a-c) Null activity (a), startle activity (b), and PPI (c) for C57BL/6J mice treated with vehicle (Veh), 5 or 10 mg/kg nuciferine (Nuc), and/or phencyclidine (PCP). (d-g) Null activity (d), startle activity (e), and PPI for wild-type (WT) (f) and dopamine transporter knockout (DAT-KO) mice (g) given Veh, 2 mg/kg clozapine (CLZ) or 2.5–10 mg/kg Nuc. N = 8–17 mice/group in the C57BL/6J experiment; *p<0.05, compared to Veh/Nuc groups; +p<0.05, compared to the Veh and PCP groups; †p<0.05, compared to all other groups. N = 9–17 mice/genotype/treatment in the DAT experiment; ^p<0.05, WT versus KO within dose; #p<0.05, dose effect within genotype; &p<0.05, overall drug effect regardless of genotype.

Analyses of responses from the DAT KO mice presented a different picture. A two-way ANOVA for null activity observed significant genotype [F(1,102) = 12.410, p<0.005] and treatment effects [F(4,102) = 18.516, p<0.001] and a significant genotype by treatment interaction [F(4,102) = 3.956, p<0.01]. Bonferroni corrections demonstrated that null activity in DAT-KO mice was higher than that in WT mice with clozapine (p<0.005) and 2.5 mg/kg nuciferine (p<0.01) (Fig 9D). Null activity in WT mice to clozapine and 5 mg/kg nuciferine were significantly enhanced relative to the vehicle control (p<0.005), whereas null activity in DAT-KO mice to clozapine and all doses of nuciferine were significantly augmented compared to vehicle group (p<0.001). A two-way ANOVA for startle responses revealed significant main effects of genotype [F(1,102) = 9.227, p<0.005] and treatment [F(4,102) = 28.673, p<0.001] (Fig 9E). Regardless of genotype, clozapine-treated mice had higher startle responses than all other groups (p<0.001). For PPI a RMANOVA found significant within-subject effects of prepulse intensity [F(2,204) = 60.090, p<0.001] and a significant prepulse intensity by genotype interaction [F(2,204) = 10.479, p<0.001]. Bonferroni tests demonstrated prepulse dependency in WT animals where inhibition at each prepulse intensity was significantly different from each other (p<0.001) (Fig 9F). By contrast, in DAT-KO animals responses to the 12 dB prepulse were higher than those to the 4 and 8 dB prepulses (p<0.005), which were not significantly distinguished from each other (Fig 9G). The between subjects test discerned significant genotype [F(1,102) = 25.246, p<0.001] and treatment effects [F(4,102) = 4.238, p<0.005] and a significant genotype by treatment interaction [F(4,102) = 3.288, p<0.05]. Bonferroni comparisons found that PPI was significantly lower for DAT-KO than WT mice in the groups given vehicle or any dose of nuciferine (p<0.05). Clozapine significantly enhanced PPI in DAT-KO mice relative to the vehicle and nuciferine treatments (p<0.05). Together, these data show that PPI is intact in WT animals and it is not affected by either clozapine or nuciferine. By contrast, PPI is deficient in DAT-KO mice and it was restored by clozapine but not by nuciferine.

3.8 Catalepsy

Nuciferine (10.0 mg/kg) did not produce catalepsy at any of the time-points examined (Table 3).

Table 3. Cataleptic properties of nuciferine.

| Post-injection timepoint (min) | Vehicle | Nuciferine10.0 mg/kg | Haloperidol1.0 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 3 ± 2.08 s | 2.3 ± 2.3 s | 270 ± 30 s |

| 60 | 2.67 ± 1.45 s | 4.7 ± 2.6 s | 300 ± 0 s |

Nuciferine did not cause a latency to move in the inclined grid test compared to haloperidol at the doses and times tested.

4. Discussion

Here we present an in vitro and in vivo characterization of nuciferine, an alkaloid found in Nelumbo nucifera and Nymphaue caerulea lotus plants. Our primary finding was that nuciferine has a pharmacological profile similar but not identical to some antipsychotic drugs (especially aripiprazole) and that nuciferine performed as an antipsychotic-like drug in some animal models predictive of antipsychotic drug-like actions. Here, we discuss these findings in the context of antipsychotic pharmacology and animal models of antipsychotic efficacy.

4.1 Molecular characterization

The in silico prediction and in vitro characterization of nuciferine revealed a molecular affinity profile containing receptors known to be modulated by established antipsychotic drugs. Within the set of 13 receptors with <1 μM affinity, nuciferine showed greatest affinity at the serotonergic receptors and overall it exhibited a molecular profile with multiple entities implicated in clinical antipsychotic efficacy: 5-HT7 [29, 34, 40, 41], 5-HT6 [34], 5-HT2A [5], 5-HT1A [42], 5-HT1D [43], D2 [44], D1, D3, D4, D5 [45], α2B, and α2C [46]. The preponderance of low affinity antagonism led us to test whether nuciferine forms colloidal aggregates. Parenthetically, colloidal aggregation is a phenomenon that affects molecular pharmacological screening efforts and has not been appreciated until relatively recently.[47] Compounds that form colloidal aggregates can present unique and irrelevant behavior in vitro [48], and we avoided these confounds by demonstrating that nuciferine does not form aggregates at concentrations up to 10 μM. Of the non-GPCR targets that SEA predicted, SK channels have been shown to bind antipsychotic compounds, [49] while VMAT2 is involved in monoaminergic neurotransmission and has long been proposed as a target for antipsychotic drug activity.[50, 51] It is also interesting to note that nuciferine does not bind to any muscarinic receptors. Muscarinic antagonists are prescribed to prevent or treat extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics. [52–54] During the course of our investigation, an independent group determined that nuciferine functions as a 5-HT2A antagonist [55], corroborating our findings at this receptor.

With respect to antipsychotic efficacy, the D2 receptor is a desired druggable target with all approved antipsychotic drugs having potent interactions with this target.[30] In addition to D2 receptor affinity, however, it is also known that partial agonists have antipsychotic efficacy, such as aripiprazole.[19, 31] Therefore, we examined the D2 functional properties of nuciferine in comparison to aripiprazole and found that nuciferine exhibited a similar degree of partial agonist activity compared to aripiprazole, suggesting that nuciferine could exhibit antipsychotic drug-like properties, albeit with lower potency. The ability to block or antagonize DA-stimulated D2 activity may be a better predictor of antipsychotic efficacy, especially in the case of D2 partial agonists such as aripiprazole with low intrinsic efficacy in vitro,[56] which may act as D2 antagonists in vivo. [57] To examine nuciferine’s antagonist activity, we chose to measure nuciferine’s ability to block DA-stimulated D2 activation using a Schild regression analysis.[32] Results indicated that nuciferine can antagonize DA-stimulated cAMP inhibition with a potency similar to clozapine. Clozapine, one of the most effective atypical antipsychotics, possesses lower affinity for the D2 receptor compared to typical antipsychotics, [5] and therefore it is conceivable that just a moderate degree of D2 antagonism is needed for antipsychotic efficacy, given that clozapine also possesses potent 5-HT2A antagonism, 5-HT1A partial agonist activity, and 5-HT7 inverse agonism, which nuciferine also possesses. In summary, nuciferine shares two properties of antipsychotic efficacy at the D2 receptor, namely partial agonist activity at the D2 receptor similar to aripiprazole, and antagonist activity with moderate affinity comparable to clozapine.

There were notable discrepancies within our study across paradigms and compared to previously published findings. For instance, the SEA predicted one entity (dopamine D5 receptor) that was not detected in the PDSP binding affinity assay but was detected in the functional assay. The micromolar efficacy of nuciferine at the D5 receptor as measured via functional assays is consistent with the low binding affinity, due to the fact that the antagonist radioligand [3H]SCH 23390 labels inactive states of the receptor. Additionally, the dopamine transporter (DAT) was neither predicted using the SEA nor was it detected in the PDSP screen, yet it was determined that nuciferine modulates the DAT in vitro using a functional assay, again suggesting that this compound may be modulating the DAT at a site other than that occupied by the radioligand [3H]WIN35428. Interestingly, our behavioral results with amphetamine in the open field also support the notion that nuciferine interacts with DAT. It was previously reported that nuciferine inhibits the hyperlocomotor effect of amphetamine [4], but in our study we observed an increase in hyperlocomotor activity following nuciferine pretreatment. Our methods differed substantially from those of Bhattacharya et al. [4] who used a considerably higher dose range (25–100 mg/kg) of nuciferine, compared to our lower dose range (1–10 mg/kg across the study with 3.0 mg/kg nuciferine in the amphetamine experiment). These discrepancies support the use of orthologous assays in screening efforts to fully elucidate a chemical’s pharmacology.

The discovery of DAT modulation occurred serendipitously during the verification of the SEA VMAT2 prediction due to the nature of the experimental system. In these experiments, nuciferine caused an increase in uptake in cells expressing DAT but showed no effect in cells expressing both DAT and VMAT2. Direct measurement of uptake in isolated vesicles failed to detect direct modulation of VMAT2 by nuciferine. The difference between the results of the DAT and DAT/VMAT2 cells suggests that nuciferine may be indirectly inhibiting vesicular uptake in the HEK-DAT/VMAT2 cells, counteracting the increased DAT-mediated uptake. This is likely an indirect modulation of VMAT2 because nuciferine did not directly affect VMAT2 uptake in the isolated vesicle assay. However, further experiments are necessary to determine the mechanism.

4.2 Behavioral characterization

Since the initial studies of Macko and colleagues, our ability to assess antipsychotic efficacy in animal models has improved. For example, deficits in sensorimotor gating observed in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are modeled in rodents using the pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) paradigm, in which the startle response to a stimulus is inhibited by a pulse of reduced magnitude preceding the acoustic startle stimulus. Deficits in PPI are observed in schizophrenia patients and can be rescued by antipsychotic medications.[58] This deficit in PPI can be reproduced in animal models via administration of phencyclidine (PCP), a compound that produces psychosis-like effects in humans, and the disrupted PPI can be rescued by antipsychotic compounds.[59, 60] Notably, the rescue of PCP-induced disruption of PPI has been a hallmark of preclinical antipsychotic drug discovery efforts as a predictive model of antipsychotic efficacy. [61]

We thus set out to determine whether the identified molecular profile would translate into antipsychotic drug-like actions as determined by several animal models commonly used to study antipsychotic pharmacology. As mentioned previously, atypical antipsychotics exhibit 5-HT2A antagonist activity, and the potency with which antagonists attenuate the head-twitch response is highly correlated with the antagonist's affinity for 5-HT2A receptors. [62, 63] The ability of nuciferine to block the hallucinogen DOI-induced head-twitch response is consistent with the in vitro measurements of 5-HT2A antagonism and suggests activity in vivo via 5-HT2A receptor blockade. Furthermore, the dissociative psychedelic PCP produces a psychomimetic state in humans and the inhibition of PCP-induced behavioral effects is used as an animal model for evaluating schizophrenia-like behaviors.[64, 65] Nuciferine blocked not only the PCP-induced hyperlocomotor activity in the open field, but it also rescued PCP-disrupted PPI without direct antagonism of the NMDA PCP binding site. Despite clozapine rescuing PPI in DAT-KO mice, nuciferine failed to normalize PPI in the DAT-KO genetic mouse model of hyperdopaminergia or in the pharmacological model using amphetamine (data not shown). At this time, the molecular basis of the distinctions between the differential responses in the hypoglutamateric and hyperdopaminergic models is obscure. To our knowledge, this is the first report of nuciferine’s efficacy in these animal models and our results indicate that this compound has greater efficacy in hypoglutamateric than in hyperdopaminergic animal models

The drug discrimination paradigm utilizes the interoceptive properties of drugs as a means to study their pharmacology. We used this paradigm to assess nuciferine’s pharmacology due to its unique ability to measure a systems-level pharmacological effect (as would be caused by a compound with high polypharmacology) at a whole organism level of analysis and due to its use in drug discovery efforts in the past.[66, 67] Nuciferine’s antagonism of the DOI-induced discriminative stimulus is consistent with its capacity to also antagonize DOI-induced head twitches and this result further validates the 5-HT2A antagonism observed in vitro. Interestingly, nuciferine did not block the PCP-induced discriminative stimulus. It should be emphasized that other investigators have reported that antipsychotics do not antagonize the discriminative stimulus of PCP. [68] Finally, nuciferine fully substituted for clozapine at the highest dose tested (10.0 mg/kg), indicating that nuciferine produced an interoceptive state similar to that of clozapine. Previous studies in C57BL/6 mice have shown that 5-HT2A serotonergic and α1-adrenoceptor antagonism mediate clozapine’s discriminative stimulus. [69] It should be noted that the 10.0 mg/kg dose of nuciferine that substituted for clozapine also produced significant rate suppression compared to vehicle control rates; however, previous studies have shown that the doses of antipsychotics that produce full substitution for clozapine are often accompanied by significant rate suppression (in both rats [70, 71] and mice[72, 73]).

4.3 Conclusion

In conclusion, we have comprehensively elucidated a complex pharmacological profile for nuciferine, one of the main alkaloids present in Nelumbo nucifera. The molecular profile of nuciferine was similar but not identical to the profiles of several approved antipsychotic drugs suggesting that nuciferine has atypical antipsychotic-like actions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the husbandry technicians involved in this work.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants #1F31MH091921 to MSF and RO1MH61887, U19MH82441, the National Institutes of Mental Health Psychoactive Drug Screening Program and the Michael Hooker Chair in Pharmacology to BLR; P30 ES 019776 and T32 ES 012870 to GWM and AIB, and and NIH GM71630 and GM71896 to BKS. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.