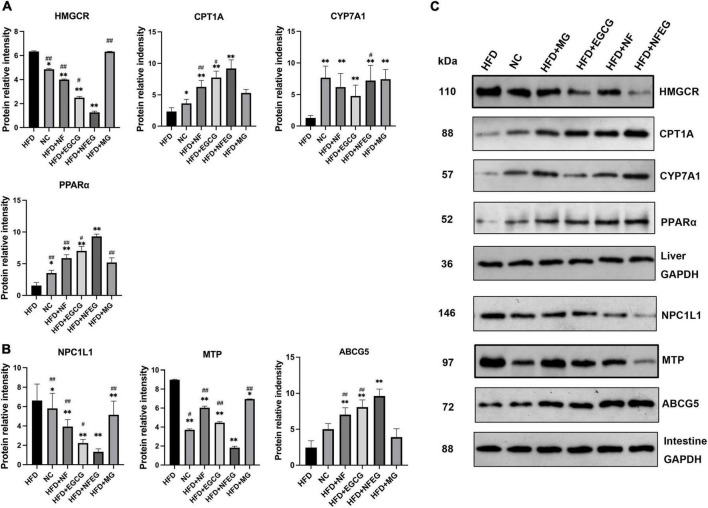

NFEG-microgel significantly regulated the protein expression of genes in liver and small intestine

Western blot was used to detect liver PPARα, CYP7A1, HMGCR, and CPT1A and small intestine NPC1L1, MTP, and ABCG5. As shown in Figure 4, differences in the expression of these proteins were observed among the groups. The protein expression levels of PPARα, CYP7A1, and CPT1A were significantly higher in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, and HFD + NFEG groups than in the HFD group (P < 0.01) and were higher in the HFD + NFEG group than in the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups (P < 0.05). The protein expression level of HMGCR was significantly higher in the HFD and HFD + MG groups than other groups (P < 0.05) where that in the HFD + NFEG group was the lower than others (P < 0.05). The protein expression levels of NPC1L1 and MTP significantly decreased in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, and HFD + NFEG groups compared with those in the HFD group (P < 0.01) and were lower in the HFD + NFEG group than in the NC, HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups (P < 0.05). The protein expression levels of ABCG5 were significantly higher in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, and HFD + NFEG groups than in the HFD group (P < 0.01) and were higher in the HFD + NFEG group than in the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups (P < 0.01). Meanwhile, the protein expression levels of PPARα, CPT1A, HMGCR, NPC1L1, and ABCG5 in the HFD + MG group showed no significant differences from those in the HFD group (P > 0.05), except for NPC1L1 and MTP (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 4.

Protein expression of genes in the liver and small intestine; the results of Western blot were almost consistent with those of qRT-PCR. (A) Protein relative intensity expression of HMGCR, CYP7A1, CPT1A, and PPARα in rat liver. (B) Protein relative intensity expression of NPC1L1, MTP, and ABCG5 in rat small intestine. (C) WB bands. (*P < 0.05) and (**P < 0.01) vs. HFD group; (#P < 0.05) and (##P < 0.01) vs. HFD + NFEG group.

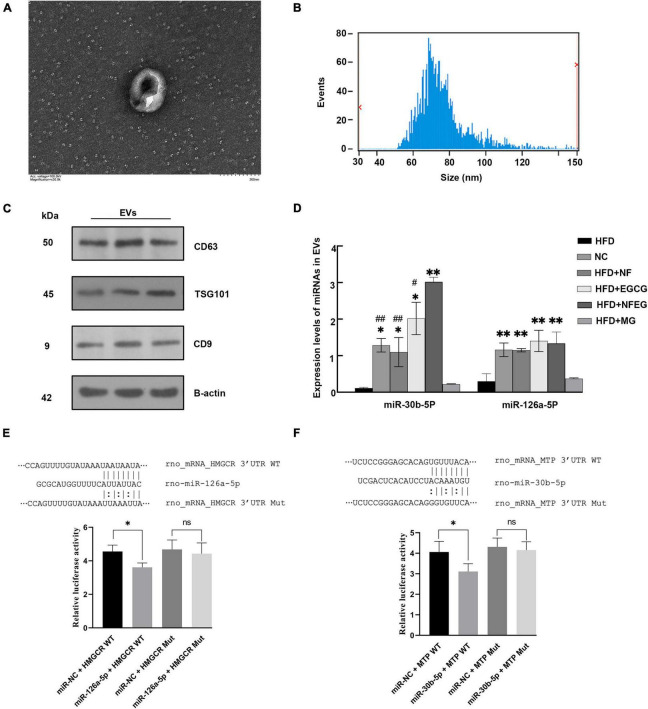

Identification of extracellular vehicles in the serum

As shown in the TEM observation in Figure 5A, the serum EVs had spherical structures and saucer shape. Their particle size range within 50–140 nm (Figure 5B), and the average particle sizes of the NC, HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + NFEG, HFD + MG, and HFD groups were 86.92, 83.71, 88.08, 96.01, 92.45, and 84.69 nm, respectively. For EV characterization, three marker proteins were reported in at least a semi-quantitative manner. Western blot analysis showed that the expression levels of the surface proteins of EVs, CD9, CD63, and TSG101 were high in the EVs (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Identification and miRNA expression level of EVs and dual-luciferase reporter assay analysis. (A) Serum EVs of different groups observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at the scale of 200 nm. (B) Particle size analysis showing that the particle size of each exosome ranged from 50 to 140 nm. (C) Expression levels of CD9, CD63, and TSG101 determined by Western blot. (D) miRNAs were extracted from rat serum EVs, and their expression levels were detected by qRT-PCR. Significant difference was indicated with the sign (*P < 0.05) and (**P < 0.01) vs. HFD group; (#P < 0.05) and (##P < 0.01) vs. HFD + NFEG group. Dual-luciferase reporter assay analysis: (E) the top portion of panel (E) shows the binding site of miR-126a-5p mimics and corresponding target genes HMGCR, and the bottom portion of panel (E) shows the relative fluorescence values after transfection and mutation, which suggested that significant interaction existed between miR-126a-5p and target gene HMGCR. Panel (F) shows similar results on the interaction of miR-30b-5p with MTP. Significant difference was indicated with the sign *P < 0.05.

NFEG-microgel significantly regulated the level of miRNA in serum extracellular vehicles

Five miRNAs closely associated with lipid metabolism were detected. Compared with those in the HFD and HFD + MG groups, the expression levels of miR-30b-5p and miR-126a-5p in the NC, HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG and HFD + NFEG groups were significantly increased (P < 0.05). No significant difference was observed in the expression level of miR-21-5p, miR-33-5p, and miR-27a-3p among the groups. In addition, the expression level of miR-30b-5p in the HFD + NFEG group was higher than that in the NC, HFD + NF, and HFD + EGCG groups (P < 0.05), and the expression level of miR-126a-5p showed no significant differences among the NC, HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, and HFD + NFEG groups (Figure 5D). In accordance with the qRT-PCR results of lipid metabolism genes in the liver and small intestine, miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p may interact with their target genes HMGCR and MTP, respectively.

Effects of NFEG-microgel on dual-luciferase assay

qRT-PCR results elucidated that the expression levels of miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p in the serum EVs significantly differed among the six treatment groups and showed negative correlation with the expression of HMGCR and MTP. TargetScan and miRDB databases predicted possible interaction sites between miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p and their target genes HMGCR and MTP mRNA, respectively. The interactions of miR-30b-5p-MTP and miR-126a-5p-HMGCR were further tested by constructing the reporter plasmids of the potential action points of HMGCR and MTP and conducting dual-luciferase reporter assay.

As shown in Figures 5E,F, the relative fluorescence value of rno-miR-126a-5p + HMGCR-WT co-transfection group were lower (P < 0.05) than that of miR-NC + HMGCR-WT co-transfection group. After HMGCR mRNA mutation, no difference in relative fluorescence value was observed between the co-transfections of miR-NC+HMGCR and rno-miR-126a-5p + HMGCR groups (P > 0.05; Figure 5E). Dual-luciferase reporter assay results of miR-30b-5p and MTP showed similar results (Figure 5F). The above results implied the existence of interaction sites for miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p and their respective target mRNAs, HMGCR and MTP. These sites may be the key to relieve NAFLD by post-transcription mechanism between miRNAs and mRNAs.

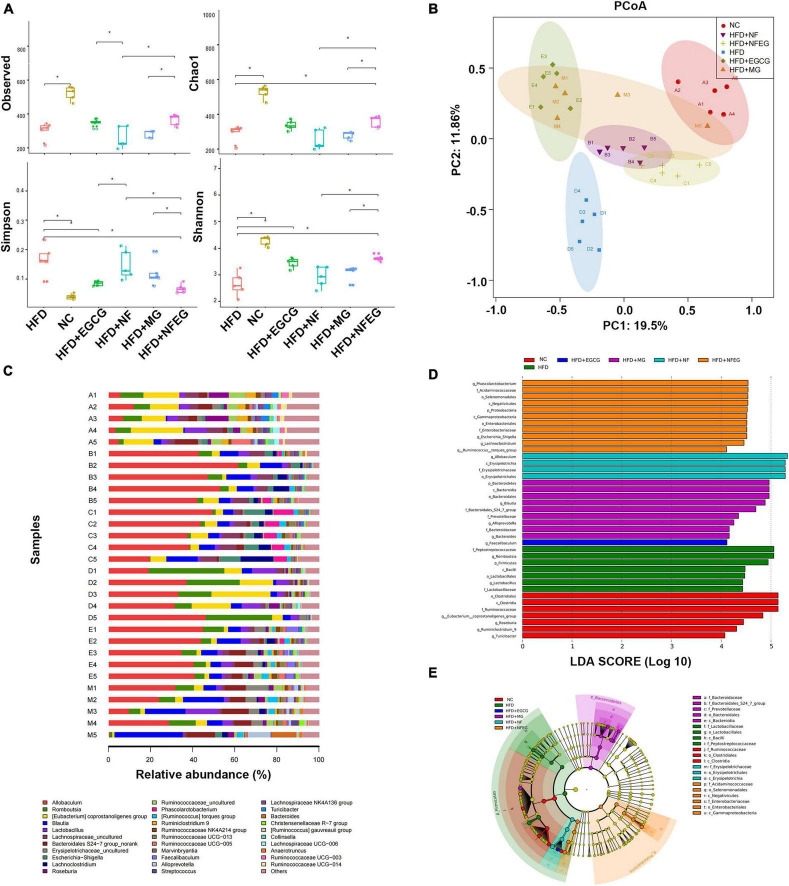

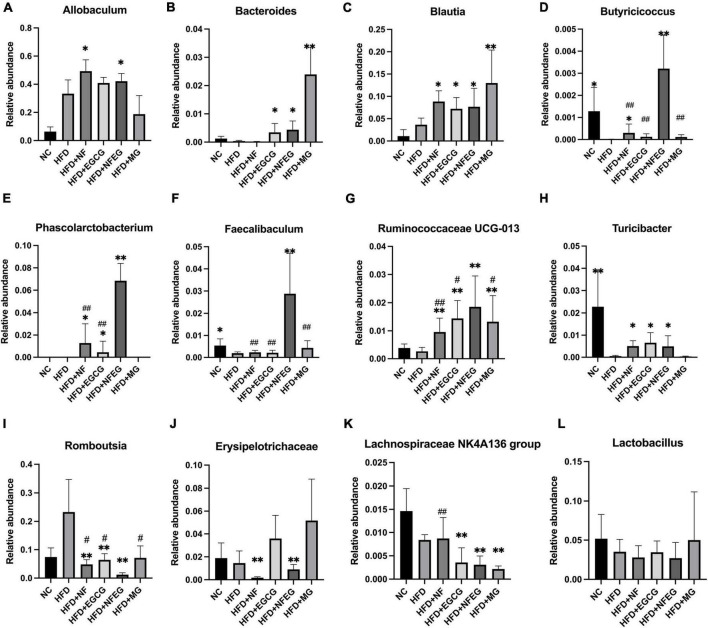

NFEG-microgel altered the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in high-fat diet rats

The gut microbiota may be an underlying target to treat obesity and related metabolic diseases. Bacterial 16S rRNA in stool was conducted to examine whether NFEG-microgel can alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Analysis of α-diversity index (Chao1 index, Shannon index, and Simpson index) reflecting gut microbiota showed that α-diversity increased with the increase in Chao1 index and Shannon index and the decrease in Simpson index (Figure 6A). Significant differences were observed among the HFD + NFEG and HFD, HFD + MG, and HFD + NF groups. Bray–Curtis PCoA analysis of OTU abundance of each rat revealed that compared with that in the NC group, the intestinal microbiota in the HFD group showed significant structural changes along the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2). Compared with the NC group, the HFD + MG and HFD + EGCG groups showed the same shift as the HFD group along PC1 whereas the HFD + NFEG group had almost the same intestinal microbiota as the NC group along both PC1 and PC2 (Figure 6B). At the genus level, high-abundance species were selected to profile the expression of each group with the heatmap in Figure 6C. From a homoplastic viewpoint, linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) method was employed to identify statistically significant biomarkers and dominant microbiota among these groups (Figures 6D,E). Unexpectedly, Firmicutes was found to be the primary phylum of the gut microbiota in the HFD group, and this finding agreed with the study of Wang et al. (5). Meanwhile, Bacterioidetes was confirmed to be the dominating phylum of the gut microbiota in the HFD + MG group. The relative abundance of Allobaculum, Blautia, Bacteroides, Butyricicoccus, Phascolarctobacterium, Faecalibaculum, Ruminococcaceae UCG-013, and Turicibacter significantly increased (p < 0.05), and that of Romboutsia, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group significantly decreased (p < 0.01). No regulatory effect on Lactobacillus was found (Figures 7A–L). Experimental results showed that NF had a significant effect on Allobaculum (Figure 7A) and Erysipelotrichaceae (Figure 7J) because it only induced significant changes in the HFD + NFEG and HFD + NF groups. NFEG-microgel significantly enriched Bacteroides, Butyricicoccus, Phascolarctobacterium, Faecalibaculum, and Ruminococcaceae UCG-013 and significantly reduced Romboutsia (P < 0.01) as which shown in Figures 7B,D–G,I. The relative abundances of these genera in the HFD + NFEG were significantly different from those in the HFD + NF, HFD + EGCG, HFD + MG, and HFD groups (P < 0.05).

FIGURE 6.

NFEG-microgel changed the diversity and composition of gut microbiota in HFD-fed rats. (A) α-diversity index (observed, Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson index). (B) Bray–Curtis PCoA plot based on the OTU abundance of each rat. (C) Heat map of bacterial taxonomic profiling at the genus level of intestinal bacteria based on each rat from different groups: NC group (A1–A5), HFD + NF group (B1–B5), HFD + NFEG group (C1–C5), HFD group (D1–D5), HFD + EGCG group (E1–E5), and HFD + MG group (M1–M5). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores (D) and cladogram (E) generated from linear discriminate analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis, showing the biomarker taxa (LDA score of > 4 and a significance of P < 0.05 determined by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Significant difference was indicated with the sign *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

FIGURE 7.

NFEG-microgel changed the relative abundance of gut microbiota in HFD-fed rats. Relative abundance of Allobaculum (A), Blautia (B), Bacteroides (C), Butyricicoccus (D), Phascolarctobacterium (E), Faecalibaculum (F), Ruminococcaceae UCG-013 (G), Turicibacter (H), Romboutsia (I), Erysipelotrichaceae (J), Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (K), and Lactobacillus (L). (*P < 0.05) and (**P < 0.01) vs. HFD group; (#P < 0.05) and (##P < 0.01) vs. HFD + NFEG group.

Discussion

Lipid metabolism involves the regulation cycle of multi-tissues, multi-genes, and multi-molecules. Therefore, microgels must contain multiple active components to improve the synergistic lipid-lowering effect. Elucidate the possible mechanism of lipid metabolism regulation from multiple ways is necessary. Chitosan is the only positively charged edible food fiber found in nature, and MLPE are negatively charged. Thus, these two can self-assemble and combine into stable microgels through electrostatic interaction. Microgel is mainly used to coat hydrophilic compounds. In our study, we first loaded NF into liposomes with hydrophilic surface and then incorporated the liposomes into the microgels, thus allowing the microgels to encapsule hydrophobic compounds. The HFD + NFEG group had significantly lower body weight, serum TC, TG, and LDL-C and significantly higher HDL-C compared with the HFD + NF and HFD + EGCG groups, proving that NF and EGCG were jointly involved in lipid regulation in the HFD rats. Most of the current research focuses on a single material carrier. The microgel prepared by using two natural materials in this study is safe, non-toxic, and has a certain lipid-lowering effect. Its preparation process is simple, and it has the advantages of embedding a variety of nutrients, which has potential application prospects in the field of food or nutrition.

Lipid accumulation in vivo is mainly related to the expression of lipid synthesis genes (such as HMGCR), lipid metabolism genes (such as PPARα, AMPK, ACC, CPT1A, and CYP7A1) in the liver, and lipid import genes (such as NPC1L1 and CD36) and lipid transporter genes (such as MTP, ABCG5, and FATP4) in the small intestine. Metabolism is regulated by reducing substrate overload to minimize the intake and transfer of metabolic substrates to metabolically active tissues. AMPK plays a central role in lipid metabolism by regulating the downstream gene ACC and CPT1 pathways. ACC catalyzes the production of malonyl-CoA, which is a major component of de novo adipogenesis and an allosteric inhibitor of CPT1 (key restriction enzyme in fatty acid β-oxidation and is also regulated by PPARα) (29). In our study, NFEG-microgel significantly increased AMPK level, decreased ACC level, and ultimately increased CPT1A function. The PPARα subtype performs its major functions in the liver, and the receptor is involved in all aspects of lipid metabolism including fatty acids (FA) transport, binding, absorption, synthesis, and oxidative degradation (30). HMGCR is a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, and CYP7A1 is a rate-limiting enzyme in the bile acid synthesis pathway; both play an important role in regulating the amount of cholesterol because bile acids provide an important excretory pathway for cholesterol metabolism (31). NPC1L1 mediates the intestinal uptake of dietary and biliary cholesterol. CD36 and FATP4 are major player in metabolic tissues and are among the proteins involved in FA uptake (32, 33). In this work, EGCG reversed the HFD-induced effects on intestinal substrate transporters CD36 and FATP4, and this finding was the same as that reported by Lu et al. (34). We found that NF and EGCG played a synergistic role in alleviating lipid accumulation. In particularly, NF mainly acted on lipid metabolism in the liver and regulated lipid transport and efflux in the intestine, and EGCG and blank microgel inhibited lipid absorption in the intestine.

As a series of post-transcriptional gene repressors, miRNAs are widely related to the regulation of gene expression, including almost all aspects of the system controlling metabolism. In regulating gene expression, miRNAs play an important role in communication. Yan et al. testified that the disruption of miR-126a in mice caused hepatocyte senescence, inflammation, and metabolism deficiency and revealed that the administration of miR-30b-5p antagonist attenuated liver inflammation in the injured liver. Zhang et al. (35) reported the increased expression of PPARα and decreased expression of lipid synthesis related gene SREBP-1 in miR-30b-5p overexpressed Huh-7 cells. Our detection results showed that the expression levels of miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p significantly differed among the six groups. Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay validated that miR-126a-5p and miR-30b-5p significantly interacted with their target genes HMGCR and MTP, respectively. The present study revealed that the miRNAs in the serum EVs target the genes associated with lipid metabolism as shown in the Graphical Abstract by Biorender.4 Therefore, the NAFLD relieving mechanism of NFEG-microgel might be related to the regulation of miRNA signaling.

Gut microbes are considered “new organs” and play an important role in metabolic disorders. Wang et al. (5) demonstrated that the abundance of Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and Erysipelotrichaceae decreased after supplementation, and this finding is consistent with our experimental results. Multiple studies revealed that Turicibacter was negatively correlated with inflammation in obesity (36, 37). Kaakoush clarified a strong association between Erysipelotrichaceae and host lipid metabolism. Wang et al. (38) revealed that HFD can reduce the abundance of Lactobacillus, Faecalibaculum, and Blautia. SCFAs may contribute to energy expenditure and appetite regulation. In addition to their role in gut health and signaling molecules, SCFAs may also affect substrate metabolism and peripheral tissue function by entering the systemic circulation. A growing body of evidence proves the benefits of SCFAs in adipose tissues and liver substrate metabolism and function (39). Zhang et al. confirmed that berberine can significantly enrich Blautia and Allobaculum, which produce SCFAs in the intestine, and consequently increase the amount of intestinal SCFAs (40).

According to the outcomes of PCoA and stratified cluster analysis, HFD feeding profound altered the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota, and NFEG-microgel significantly improved the intestinal microbiota dysbiosis in rats. NFEG-microgel significantly enriched the bacteria that produce SCFAs, including Allobaculum, Blautia, Bacteroides, Butyricicoccus, Phascolarctobacterium (41), Romboutsia, and Faecalibaculum (42), suggesting that these SCFA-producing bacteria play an important role in the efficacy of NFEG-microgel.

However, we only broadly illustrated the association, but not the causality, between the improved gut microbiota and the anti-obesity effects of NFEG-microgel. Further studies with feces transplantation experiments are necessary to clarify this association. Additionally, chitosan and proanthocyanidins were used to prepare microgels, which proved to be stable and effective, but the molecular mechanism of their binding still needs to be further explored. In addition, the source and production mechanism of EVs need further study.

In conclusion, NFEG-microgel could prominently inhibit the development of NAFLD and its related metabolic alterations by suppressing body weight gain, reducing serum lipids, ameliorating hepatic injury, and regulating the genes associated with lipid metabolism and miRNA increase. Furthermore, NFEG-microgel increases the diversity of gut bacterial community and the relative contents of beneficial bacteria and decreases the abundance of pathogenic bacteria. This generalizable strategy of encapsulating multiple nutrients in porous microgels using chitosan and MLPE can be applied in other systems to achieve the synergistic effects of multiple nutrients. NFEG-microgel offers an effective and innovative treatment of dyslipidemia.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA882230.

Ethics statement

This animal study was reviewed and approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee from China Jiliang University under the approval number: 2022-005.

Author contributions

SZ designed the experimental scheme, performed the experiment operation, analyzed the data, and finished the manuscript. WX completed parts of experiments including oral administration and took samples of the rats. JG guided and supervised the whole experimental process. JL, FG, AX, and JZ also provided some guidance and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to thank Jingwu Song, Zonghua Dong, Luting Ye, Zhaowei Chen, Simin Ren, Min Cheng, and Xuanxuan Zou (College of Life Sciences, China Jiliang University) for generously providing rats administration. Financial assistance from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Major Science and Technology Projects in Zhejiang Province are sincerely thanked.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100499 and 31672394), the Major Science and Technology Projects in Zhejiang Province (2020C02045), and Zhejiang Science and Technology Commissioner Team Project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.1069797/full#supplementary-material

Morphological observation of liver.